Being completely honest, this stupid simple child play in truth is a very important and valuable data collection.

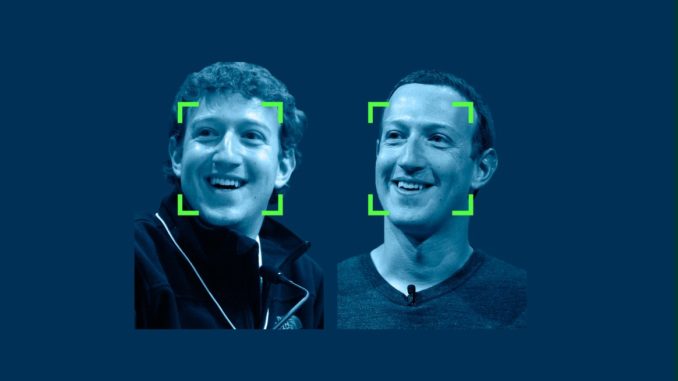

In one week the social networking and medias had a challange on collect picture of almost every user to put a new picture and a 10 years ago picture in Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. This intent is to promote data collection on compare the present and past and stimulate a new artificial inteligence on how to promote an aging compare and map people around the world, with the hacking of webcams and also, for a tool that 10 years ago didn't have in the social medias. So, now on this can track terrorism activities, economic transactions, facial reconigtion on daily life and mapping the world wide social life.

With all this data and information, these social networking medias could have built a giant database and being used to train algorithms of facial reconigtion, understant the aging of people, progression on daily life and changing, also, train this algorithms to promote facial reconigtion of new criminal activities, not only for international terrorism, but to promote a map of everyone, and promote the capability of test a possible future facial appearance.

this free world of freedom of speak, fake news, the limit is inside the everyones confidence and all the care you can take is few, compared to the capability and power of those behind, like Zuckerberg is one of the world's most powerful man, because he has all this information to sell to military activities hired by groups like C.I.A. and indirectly Bilderberg or Rothschilds, George Soros, Microsoft and his own financial philantropic organization's proposes, promoting a world control by a simple play.

Take care on these harmless jokes of internet that these groups can launch.

Is Facebook’s ’10 Year Challenge’ Really About Training Facial Recognition AI?

https://newspunch.com/is-facebooks-10-year-challenge-really-about-training-facial-recognition-ai/

The latest ’10 year challenge’ meme currently going around Facebook and Instagram might actually be a data mining experiment designed to train facial recognition algorithms on age progression and age recognition.

According to technology expert Kate O’Neill, the public may be unwittingly helping Facebook to train their facial recognition robots, granting the social media giant even more access to our private lives.

Wired.com reports: It’s worth considering the depth and breadth of the personal data we share without reservations.

Of those who were critical of my thesis, many argued that the pictures were already available anyway. The most common rebuttal was: “That data is already available. Facebook’s already got all the profile pictures.”

Of course they do. In various versions of the meme, people were instructed to post their first profile picture alongside their current profile picture, or a picture from 10 years ago alongside their current profile picture. So, yes: These profile pictures exist, they’ve got upload time stamps, many people have a lot of them, and for the most part they’re publicly accessible.

But let’s play out this idea.

Imagine that you wanted to train a facial recognition algorithm on age-related characteristics and, more specifically, on age progression (e.g., how people are likely to look as they get older). Ideally, you’d want a broad and rigorous dataset with lots of people’s pictures. It would help if you knew they were taken a fixed number of years apart—say, 10 years.

Sure, you could mine Facebook for profile pictures and look at posting dates or EXIF data. But that whole set of profile pictures could end up generating a lot of useless noise. People don’t reliably upload pictures in chronological order, and it’s not uncommon for users to post pictures of something other than themselves as a profile picture. A quick glance through my Facebook friends’ profile pictures shows a friend’s dog who just died, several cartoons, word images, abstract patterns, and more.

In other words, it would help if you had a clean, simple, helpfully labeled set of then-and-now photos.

What’s more, for the profile pictures on Facebook, the photo posting date wouldn’t necessarily match the date the picture was taken. Even the EXIF metadata on the photo wouldn’t always be reliable for assessing that date.

Why? People could have scanned offline photos. They might have uploaded pictures multiple times over years. Some people resort to uploading screenshots of pictures found elsewhere online. Some platforms strip EXIF data for privacy.

Through the Facebook meme, most people have been helpfully adding that context back in (“me in 2008 and me in 2018”) as well as further info, in many cases, about where and how the pic was taken (“2008 at University of Whatever, taken by Joe; 2018 visiting New City for this year’s such-and-such event”).

In other words, thanks to this meme, there’s now a very large dataset of carefully curated photos of people from roughly 10 years ago and now.

Of course, not all the dismissive comments in my Twitter mentions were about the pictures being already available; some critics noted that there was too much crap data to be usable. But data researchers and scientists know how to account for this. As with hashtags that go viral, you can generally place more trust in the validity of data earlier on in the trend or campaign—before people begin to participate ironically or attempt to hijack the hashtag for irrelevant purposes.

As for bogus pictures, image recognition algorithms are plenty sophisticated enough to pick out a human face. If you uploaded an image of a cat 10 years ago and now—as one of my friends did, adorably—that particular sample would be easy to throw out.

For its part, Facebook denies having any hand in the #10YearChallenge. “This is a user-generated meme that went viral on its own,” a Facebook spokesperson responded. “Facebook did not start this trend, and the meme uses photos that already exist on Facebook. Facebook gains nothing from this meme (besides reminding us of the questionable fashion trends of 2009). As a reminder, Facebook users can choose to turn facial recognition on or off at any time.”

But even if this particular meme isn’t a case of social engineering, the past few years have been rife with examples of social games and memes designed to extract and collect data. Just think of the mass data extraction of more than 70 million US Facebook users performed by Cambridge Analytica.

Is it bad that someone could use your Facebook photos to train a facial recognition algorithm? Not necessarily; in a way, it’s inevitable. Still, the broader takeaway here is that we need to approach our interactions with technology mindful of the data we generate and how it can be used at scale. I’ll offer three plausible use cases for facial recognition: one respectable, one mundane, and one risky.

The benign scenario: Facial recognition technology, specifically age progression capability, could help with finding missing kids. Last year police in New Delhi reported tracking down nearly 3,000 missing kids in just four days using facial recognition technology. If the kids had been missing a while, they would likely look a little different from the last known photo of them, so a reliable age progression algorithm could be genuinely helpful here.

Facial recognition’s potential is mostly mundane: Age recognition is probably most useful for targeted advertising. Ad displays that incorporate cameras or sensors and can adapt their messaging for age-group demographics (as well as other visually recognizable characteristics and discernible contexts) will likely be commonplace before very long. That application isn’t very exciting, but stands to make advertising more relevant. But as that data flows downstream and becomes enmeshed with our location tracking, response and purchase behavior, and other signals, it could bring about some genuinely creepy interactions.

Like most emerging technology, there’s a chance of fraught consequences. Age progression could someday factor into insurance assessment and health care. For example, if you seem to be aging faster than your cohorts, perhaps you’re not a very good insurance risk. You may pay more or be denied coverage.

After Amazon introduced real-time facial recognition services in late 2016, they began selling those services to law enforcement and government agencies, such as the police departments in Orlando and Washington County, Oregon. But the technology raises major privacy concerns; the police could use the technology not only to track people who are suspected of having committed crimes, but also people who are not committing crimes, such as protesters and others whom the police deem a nuisance.

The American Civil Liberties Union asked Amazon to stop selling this service. So did a portion of Amazon’s shareholders and employees, who asked Amazon to halt the service, citing concerns for the company’s valuation and reputation.

It’s tough to overstate the fullness of how technology stands to impact humanity. The opportunity exists for us to make it better, but to do that we also must recognize some of the ways in which it can get worse. Once we understand the issues, it’s up to all of us to weigh in.

So is this such a big deal? Are bad things going to happen because you posted some already-public profile pictures to your wall? Is it dangerous to train facial recognition algorithms for age progression and age recognition? Not exactly.

Regardless of the origin or intent behind this meme, we must all become savvier about the data we create and share, the access we grant to it, and the implications for its use. If the context was a game that explicitly stated that it was collecting pairs of then-and-now photos for age progression research, you could choose to participate with an awareness of who was supposed to have access to the photos and for what purpose.

The broader message, removed from the specifics of any one meme or even any one social platform, is that humans are the richest data sources for most of the technology emerging in the world. We should know this, and proceed with due diligence and sophistication.

Humans are the connective link between the physical and digital worlds. Human interactions are the majority of what makes the Internet of Things interesting. Our data is the fuel that makes businesses smarter and more profitable.

We should demand that businesses treat our data with due respect, by all means. But we also need to treat our own data with respect.

Is #10YearChallenge dangerous for our privacy?

https://nexter.org/10-year-challenge-ai-training-harmful-privacy

https://nexter.org/10-year-challenge-ai-training-harmful-privacy

People adore challenges and sharing their own pictures so the appearing of #10yearchallenge was the question of time.

The #10YearChallenge goes by many names: the #HowHardDidAgingHitYou challenge, the aging challenge and #GlowUp challenge, though the trend has picked up the most speed as the #10YearChallenge. Participants simply post two images – usually side by side – which were taken at least ten years apart.

Participating in the challenge is pretty easy. All you have to do is share two side by side photographs of you ten years apart, then post it to your Facebook/Instagram account with the hashtag #10YearChallenge, though some people just choose to post a single throwback shot.

However, after weeks of people actively participating in the challenge, Wired Magazine writer Kate O’Neill posted a sarcastic tweet on “how all this data could be mined to train facial recognition algorithms on age progression and age recognition.”

And that is when all the theories began.

O’Neill also added for Wired article, “Thanks to this meme, there’s now a very large dataset of carefully curated photos of people from roughly 10 years ago and now.

But even if this particular meme isn’t a case of social engineering, the past few years have been rife with examples of social games and memes designed to extract and collect data. Just think of the mass data extraction of more than 70 million US Facebook users performed by Cambridge Analytica.”

Facebook didn’t comment much on this topic and only rejected the accusations.

“The 10-year challenge is a user-generated meme that started on its own, without our involvement,” the company said. “It’s evidence of the fun people have on Facebook, and that’s it.”

Though it’s not necessarily bad. For instance, some of the features of facial recognition might help in the future to find missing people (like China uses the technology to look for kids).